By

Lenard MILICHJune, 2009

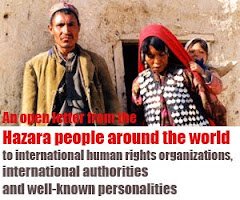

Not only severely hampered by weak government and judicial branches, a barely nascent civil society, and the Taliban insurrection, Afghanistan now also faces inter-tribal skirmishes in its formerly peaceful (and pro-government) Central Highlands, where transhumant pastoralists known by the term "Kuchi," the vast majority of whom are ethnically Pashtun and Sunni, bring their flocks each summer for highland grazing in the homeland of the Shi'a Hazara. The great danger of these armed clashes, which have left a few score people dead on both sides, Hazara houses burned, and last year generated some 60,000 internally displaced persons (IDPs), is that both sides are exhibiting an intransigence that bodes ill for the future. The Hazara have been among the most pro-government of Afghanistan's tribes, and have willingly acceded to the drive for disarmament. They feel betrayed by government inaction, and are preparing themselves for escalating the conflict with the Kuchi as necessary this summer. That perhaps one-quarter of the capital's residents are Hazara threatens to bring Kabul to a standstill, as occurred last summer for one day when an estimated 50,000 Hazara demonstrated in the city center.

At first sight, the Kuchi-Hazara conflict seems to be a quintessential struggle over access to ecological resources - that is, summer grazing. As with so many aspects of Afghanistan, competition over grazing is only the surface veneer. The roots of the conflict go back much further. Nor can the conflict be separated from the very real, but never acknowledged, issue of burgeoning population, coupled with a relatively slow rural-urban migration. Most of Afghanistan's population remains rural - an estimated 80%. Were the country endowed with superior soil and water attributes, this would not necessarily be a contentious issue. But it is not - just 5.5% of the land area consists of irrigated land. As a result, sedentary farming populations subdividing irrigated plots over generations has forced the rural populace into attempting rainfed agriculture on the surrounding hill slopes whenever the residual soil water content from winter snows and spring rainfall permit, which has been infrequent over the past decade in many parts of the country. It is this agrarian expansion that impinges on the use rights of Kuchi pastoralists, fomenting conflict as crops are damaged and grazing areas reduced in size. In turn, the Kuchi believe that all descendents of the families granted grazing rights are entitled to bring their livestock to the summer grazing grounds.

The potential for conflict driven by competition over scarce natural resources cannot be downplayed anywhere in the country. Population data are highly unreliable; there has never been a national census, and the probability of one being held anytime in the next few years is near zero. Estimates from different sources project the country to be home to between 23 and 32 million people. Central Statistical Office population statistics are therefore sheer guesswork, but one number does deserve attention: between 2003 and 2004, CSO figures suggest the population to have increased by 4.4%. Most refugee returnees went home the previous year, and the 700,000 Afghans deported from Iran arrived in later years. Hence, the 4.4% may be CSO's best guess for natural population growth. What is immensely alarming about this figure is that it predicts population doubling in 16.5 years. If in the ballpark, then such growth rates demand a paradigm shift in the business-as-usual development scenarios being constructed by the government and donor partners.

Lastly, casual observers of Afghanistan's history might conclude that the country's monarchy ended with Zahir Shah's abdication in 1973 or perhaps with his death in 2007. They would be wrong because ethnicity was, is, and for the foreseeable future will continue to be, King. And as with any monarch more than merely a constitutional figurehead, viziers vie for influence through political manipulation and intrigue. The swirl of Afghan history of the past 120 years underlie the Behsud conflicts, and it is these manipulative intrigues, summed over this period, that make this particular conflict - and by extension, most Kuchi-Hazara contests over land - intractable to community-based dispute resolution mechanisms.

This paper reports on the themes and details covered by a series of key informant interviews conducted by staff of the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit in late 2008 and early 2009 among prominent and ordinary Kuchis and Hazaras, as well as high-placed Afghan civil servants, international and national staff of UN agencies, and involved NGOs. The regrettable imperative to protect informants' identities means that no individuals can be identified in this report. Furthermore, while throughout these interviews triangulation or confirmation of information freely provided was a priority, a final effort to separate fact from fictional rumor cannot be accomplished. But in the author's view, such separation is, ultimately, unnecessary, because what drives the Behsud conflict is a very strong feeling of righteousness on both sides, rather than cool analysis on anyone's part - except perhaps those of the "King's viziers."

To reiterate, it is incumbent on readers of this document to exercise appropriate judgment with respect to the background section. For example, allegations of severe bias on the part of an organ of the Afghan state may not be substantiated under independent external review; nonetheless, this does not detract from the fact that an involved party strongly perceives that a bias exists, which then affects its subsequent belief systems, responses, and future behaviors.

Background: Elements of the Conflict

Afghanistan, as is well known, has suffered through repeated cycles of violence and warfare for more than two millenia. The current Behsud conflict can be traced back to Royal policy of the late 19th century. Abdur Rahman Khan, Emir of Afghanistan between 1880 and 1901, is justifiably known by the appellation "The Iron Emir," for he crushed, not only suppressed, any attempt to question his authority. In 1892, Abdur Rahman put an end to the Hazara insurrection, which had started in the late 1880s. To assist with the pacification of Hazarajat, Abdur Rahman dispatched Sunni clerics to the area, in an attempt to rid it of Shi'ism; he instituted burdensome taxation on the Hazaras; and his divide-and-rule policies abetted the sale of Hazara men and women into de facto slavery - a situation formally ended by a declaration of the illegality of slavery in 1923. To justify his actions, he is said to have gathered Sunni mullahs in Kandahar, after which they declared the Hazara to be kaffir, i.e., infidels. To gain political control over the fractious Hazara, the Iron Emir commenced the "Afghanization" of Hazarajat, encouraging the settling of the land and use of its pastures by Pashtu speakers, notably from the Ghilzai tribe. His local administrators issued firmans (royal decrees) that formalized access rights of Pashtun Kuchis to summer pasture land. Within these firmans, boundaries were delineated, and individual families having these access rights were listed.

Examples of firmans and two pages from Volume 3 of Seraj-al Tawarikh by Faiz Mohammad Kateb that discusses deeded Pashtun lands in Hazarajat.

The Kuchis contend that their transhumance has been occurring for 300 or more years, and that the firmans merely formalize their activities. They believe that the firmans grant the right to all descendants of the original families list to use the pastures, and claim that these pastures' boundaries are being violated by Hazara encroachment, both for rainfed agriculture and for grazing.

While these firmans were imposed from top-down on the Hazara population, for many decades thereafter, there was little in the way of resistance to Kuchi entry to summer grazing lands. Demoralized and marginalized, the Hazara chose in the main to accept the status quo, while many focused on education and/or migration as a means to a better life. Moreover, Kuchi pastoralists were often the sole source of contact for geographically and socially isolated households in the Central Highlands, arriving each summer with goods to sell or trade, albeit often the terms of trade were unfairly skewed in their favor. The inability of the Hazara to repay Kuchi loans not infrequently resulted in additional land coming under Kuchi ownership.

Kuchi transhumance into Hazarajat slowed or stopped entirely during the civil war, and many Kuchi sedenterized. Because of this vacuum, in some places local Hazara used Kuchi pasture land for rainfed agriculture, and sometimes stopped paying rent to Kuchi landowners. Livestock numbers fluctuated: in 1976, there were nationwide perhaps 23.3 million small ruminants (sheep and goats), rising (according to UN-FAO estimates) in 1995 at the beginning of the Taliban period to around 31 million, then falling to <20>

Concomitantly, the common themes among the Hazaras interviewed are that the firmans are illegitimate, having been issued in an era of despotism; that the Kuchi "are not the original Kuchi" - meaning that there are both non-Kuchis embedded in the incoming groups (this accusation is primarily focused on the belief that the Kuchi have been accused in the past of supporting the Taliban) as well as many non-Kuchi animals that are being collected for pasturing in Hazarajat; and that in any case, population growth among the Hazara has increased the demand on arable land, grazing, and water resources such that there is no longer the carrying capacity to supply food and water to both groups and their animals. In other words, Kuchi transhumance is perceived as adversely affecting the Hazara's right to a decent and secure livelihood, and this is exacerbated by the view that Pashtun Kuchis (as opposed to Arab Kuchis, who pay a head tax per animal for summer pastures in Yawkawlang) act with impunity, not taking sufficient measures to prevent damage to Hazara crops by their animals. There is, it appears, a growing sentiment in Hazarajat - at least among the educated classes as well as traditional and political leaders - that Kuchi transhumance will no longer be tolerated. Conversely, many Hazara state that Kuchi landowners are welcome in Hazarajat, but many also add the proviso that they should reside there year-round.

Most Hazara informants believe that as far as Behsud is concerned, both the Afghan National Army (ANA) and the government-appointed Sabaoun Commission (tasked with investigating the conflict) are biased in favor of the Kuchis. On the other hand, several praised the work of the Afghan National Police (ANP), pointing out that not only did the police protect individuals but also in areas under their control, they maintained cultivated land and livestock left behind by IDPs.

Information provided by national staff working for the United Nations is that Hazaras now contend that the current Pashtun-dominated government has always favored the Kuchis; the government's credibility is at rock-bottom in Hazarajat. The Hazara people have abandoned hope that the government is benevolent, and are taking steps to defend themselves. One Agency has heard of "commitments" from individual businessmen "abroad" (i.e., outside of Hazarajat) to help in this defense. Another marker of escalation is that many Hazara communities have continued to pay rent to their Kuchi landlords, and now some agitation is commencing to persuade people to stop these payments. There is an allegation that a "land tax" is being imposed to gather the financial resources to buy weapons and pay for militias. These are early signs that a conflict that breaks out in Behsud this year could rapidly spread across the Central Highlands, but not necessarily stop there, as connoted by the large Hazara demonstration in Kabul last year against the killings in Behsud.

Given such divergent views between Kuchis and Hazara, it is difficult to conceive of a reconciliation between the parties being plausible at present; in fact, because of heightened tensions, conversation itself may be impossible. The dispute can only be resolved by an essentially political decision. And this, therefore, is the paradox of Behsud, and by extension, other Kuchi-Hazara conflicts: Conflict prevention this year is purely a political decision, while simultaneous stringent depoliticization is required to defuse the underlying tensions that are likely to result in a flare-up of the conflict this or subsequent summers - a situation that could then easily spread to other areas in the Central Highlands as well as erupt in Kabul itself. Once a level of depoliticization is reached, the people who actually have ties to the land are more likely to be able to sit together and come to an agreement. For the interim, however, the recommendations below, if implemented, could extinguish the spark that could erupt into armed clashes this summer, and subsequently build a base for a final resolution in the near future.

A Glance at the Afghan Legal Environment

Article 14 of the 2004 Constitution stipulates that the State "shall design and implement... effective programs for the... settlement and living conditions of the nomads." It is this statement regarding "settlement" -inserted by a prominent Kuchi leader - that offers a realizable, albeit not immediate, resolution to the conflict between transhumant herders and sedentary farmers. The Draft Land Policy (English), dated 1385, offers broad guidance as to how this can happen. Section 3.1.8 opines that "...any approach to sustainable dispute resolution must address the historical and underlying grievances associated with how land was acquired whether by government..." - that is, it suggests that land- or usufruct-granting firmans issued during Abdur Rahman's reign can be analyzed for legitimacy under terms defined by today's more open, democratic society. How should this be carried forward? Section 2.2.6 informs us that "It is national policy that the resolution to complex issues of ownership and access rights to pasture lands be examined at the provincial level and traditional use rights of settled farmers and pastoralists established and respected." Realistically, provincial-level determinations will be untenable given the animosity felt by Hazaras toward Kuchis, hence other solutions acceptable to both parties must be implemented. Finally, land can be allocated to settle Kuchi families, as stipulated by Section 3.1.1 of the Draft Policy: "It is national policy that land distribution schemes for productive and economic activities be balanced to evenly serve the competing interest of all segments of society." The Civil Law of the Republic of Afghanistan (1975), Article 483, allows for reallocation of public lands to private use: Public property shall be deemed non-public when the period of its use in the public interest expires. These indicative mechanisms would need to be fleshed out by legal experts within the Ministry of Justice.

Many of the recommendations below are predicated upon the issuing of a Presidential firman. Under Article 79 of the Constitution, the President may issue a firman (one unrelated to financial or budgetary affairs) if the Wolesi Jirga (the Lower House of Parliament) is in recess and the situation is deemed to be an emergency. The next parliamentary recess is scheduled to begin on 15 Jawza 1388 (5 June 2009). The firman could be valid for at least 10 weeks; Article 79 stipulates that such a firman must be submitted to the National Assembly (i.e., both Houses of the Parliament) no later than 30 days after it reconvenes (recesses are of 6 weeks duration.) The firman can be based on enforcing the Law on Firearms, Equipments and Explosive Materials (Issue #855 of the Official Gazette, dates 21 June 2005), which states that anyone other than the ANA, ANP, or NDS (the intelligence service) must be licensed to carry a weapon. Article 134 of the Constitution specifies that it is the duty of the ANP to enforce the law, and the Attorney's Office to prosecute violators.

Suggestions for an Integrated Strategy to Defuse the Potential for Conflict in 2009 and Beyond

Because the chances of getting an ethnically divided and fractious Parliament to agree on legislation addressing the conflict is, in reality, impossible in the time remaining before the Kuchi are set to arrive in Behsud in May, there is only one legal avenue available: The President must issue a firman: he must state very clearly that no resumption of hostilities will be tolerated, and that the full power of the State will be brought to bear on either side should armed conflict be instigated. Karzai is allowed by the constitution to do so once the parliamentary session ends, and the firman remains valid until 30 days after parliament reconvenes without need for parliamentary endorsement.

This firman must allow the Kuchi access to Behsud through clearly delineated corridors, around which there should be a buffer zone of 500 meters on either side where no weapons can be visibly carried by either Kuchi or Hazara, as per the Law on Firearms, Equipments, and Explosive Materials (dated 21 June 2005). This firman should clarify that violators of the Law and this prohibition on visible weapons are subject to immediate arrest by any of the three branches of the Police (criminal, civil order, and justice).

The firman must specify payment of a "head tax" on every Kuchi animal that transits the Behsud area and the defile of the Jalriz Valley, with money being paid to the District Commissioner (woloswali) or other trusted recipient for subsequent equitable distribution to local communities. Concomitantly, the firman should remind the Hazara that any land deeded as "owned" by the Kuchi should be accessible to the owners at any time, in accordance with Article 40 of the Constitution.

These, however, are only temporary solutions, and do not address the natural resource issues. This can be achieved only through a broad set of initiatives. Following stabilization of the Government as an outcome of the August election, the President should convene a Distinguished Panel consisting of Ministers, legal and technical experts, and traditional representatives (including renowned figures in Shariat and customary law) to decide what is to be done with the firmans granting pastoral use rights (usufruct) during Abdur Rahman's reign. This strategy could be predicated on Article 162 of the Constitution, which states that decrees (firmans) contrary to the provisions of the Constitution (i.e., Article 14, which stipulates Kuchi settlement) are rendered invalid. One possibility could be consideration of the term "unjust" or "just," rather than "illegal" or "legal" to avoid any subsequent compensation claims, as implemented in Spain's recent examination of Franco-era policies.

Since the contribution of the Kuchi to Afghanistan's economy remains poorly understood, the Ministry of Agriculture, Irrigation, and Livestock (MAIL), together with the Ministry of Tribal Affairs / Department of Kuchi Affairs, should undertake an assessment of the magnitude of the Kuchi's input, both for food security (particularly for urban areas) and provision of livelihoods (through secondary products including fibers, pelts, and skins). Results should drive future policies. One example is that for those Kuchis continuing a traditional lifestyle, integration of methods pioneered by the Pastoral Engagement, Adaptation, and Capacity Enhancement (PEACE) Project (http://www.afghanpeace.org/) could inform them where they can go to find optimal summer pastures. For those Kuchis choosing to remain in winter locations over the summer, para-vets or other extension experts can provide advice on the management and housing of animals. None of this needs be carried out in isolation, for Afghanistan can learn from Iran's set of experience with transhumant pastoralists (locally managed agreements, legislative actions, enforcement methods, etc.).

Lenard Milich earned his PhD in Arid Lands Resource Sciences in 1997; he subsequently served with the UN World Food Programme in Asia and Africa as a vulnerability analyst, founded Africa Biofuel and Emission Reduction Company in Tanzania, and was senior research manager for natural resources at the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit when investigating the Behsud conflict. He may be contacted at lenmilich@unforgettable.com

To see the Source click: The EurasiaCritic.com

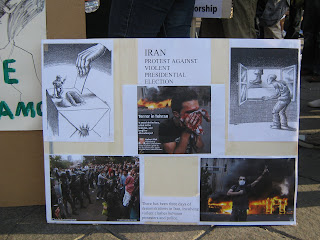

Read More about the violence against The Hazaras

The Drum of Democracy is played once again this year!

A day and half in RomeThe Afghans in Italy; Stop genocide in Afghanistan!Afshar massacre a sear on the hearts of thousandsSee CBC TV report on the Hazaras of Afghanistan The Hazaras abandon the ANA (Afghan National Army)Will Bashardost be an Obama for Afghanistan?!!When will another Mazari be born?Let Obama know about the Pashtoon Racism in AfghanistanExclusive Pictures of Kabul Protest Against Kuchi Invasion of Behsud Policing AfghanistanA review of "The Kite Runner" movieFollow Kabul Press for the latest analysis and reports on Afghanistan and the important regional issuesVisit Deedenow Cinema for the updates on Afghan Cinema and Arts